As transportation developed in the 1930s, traveling farther became more practical, which allowed a new system of free public schools to emerge. These schools were born through the consolidation of smaller school districts into larger districts, which ultimately offered a more diverse education.

Our exclusive, award-winning book, “Callaway Chalkboards: Remembering Callaway County’s Rural Schoolhouses,” offers a rich look into the one-room school experience.

The last of Callaway County’s one-room schools closed by the early 1970s, but the Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society preserves their history by constantly increasing its archives of relevant information, photographs, and reference material. We welcome donations, including:

School photos

Board minutes

Teachers’ registers

Personal stories

The KCHS Research Center has a small repository of school board minutes and teachers’ registers and is working on compiling lists of past teachers and students. If you have photos or information to add to our collection, please email research@callawaymohistory.org, or deliver to 106 East 4th Street, Fulton, Missouri 65251.

Well into the 1960s, if you were a child in rural Callaway County, odds are good you received your education in a one-room schoolhouse. In a single room, one teacher would instruct students, grades one through eight, spending 10 minutes teaching the first grade class before moving on to second. On and on it went until the teacher had finished the lesson plans for all eight grades. Then, the teacher would start again with the first grade on a different subject.

A class portrait of Oak Grove School in Bachelor, taken in 1915.

Eight grades, one room, with one teacher teaching 20, 30, 40 students—some years, even more. In 1922, seven school districts had more than 80 students. lt's hard today to imagine that such a system would work. But ask adults who grew up in these one-room schools and they will tell you they received a great education.

Today we might look at such schools as primitive and rudimentary, but for a county whose residents were farmers in remote areas, they were a natural part of the landscape. Students went to the same one-room schools their parents, grandparents, and even great grandparents had attended. Many schools could trace their history into the mid-1880s.

Callaway County had its "town schools"—Fulton, New Bloomfield, Mokane, Auxvasse, and Cedar City—but rural schools had them far outnumbered. During most of the 1900s, the Callaway County had 116 one-room schoolhouses, each locally run with board members who hired the teacher, set the salaries and determined the number of months in a term. A county superintendent guided the boards and teachers to ensure students received a proper education.

Salaries for teachers was meager. In the early 1900s, a teacher was paid about $25 a month. By the 1930s and 1940s, $50 or $60 a month. And by the 1950s, $200 to $300 a month.

Despite low pay, rural teachers were highly regarded in their communities and served as role models for young students. The work was hard, but students were always ready to pitch in. "It was a privilege to be chosen to do chores around the schoolhouse," said Helen Weigle Danuser, who taught at Middle River School. "Most were anxious to please the teacher by washing the blackboard, dusting erasers and acting as monitors to pass out papers and books when asked. All of these things helped the teacher to budget her time, as there were many things to accomplish every school day."

Schools were often close enough to farmhouses that students in the early days often walked or rode their horses to school. Once at school, the older students helped the teacher get ready for the day—drawing water from the well and filling the water crock inside, watching over younger children as they played before school started, and seeing that the stove was fired up and going.

Jr. Byrd who went to Boyd School.

When the teacher rang the bell, students came inside and sat in their desks. When all was quiet, they rose to recite the pledge of allegiance followed by the Lord's prayer. The rooms were simple. A desk for the teacher, the blackboard behind her. (In the earliest days, many teachers were men, thought better equipped to handle the rowdy farm boys.) Above the blackboard was the alphabet, both upper and lower case, and both roman and script. A large world globe stood on a shelf, as did a dictionary. The library shelf didn't have many books, but it had age-appropriate books on U.S. heroes—George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and many others.

Two outhouses stood at the edges of the schoolhouse property, one on one edge of the schoolhouse for the girls, another on the other side for the boys.

During the school day, the one-room schoolhouse had an advantage that today's schools lack: Student-to-student tutoring. When fourth grade students were finished with their assignments, for example, they would buddy up with third and second graders to help them with their assignments. Not only was it help for the younger students, but it reinforced knowledge for the older students.

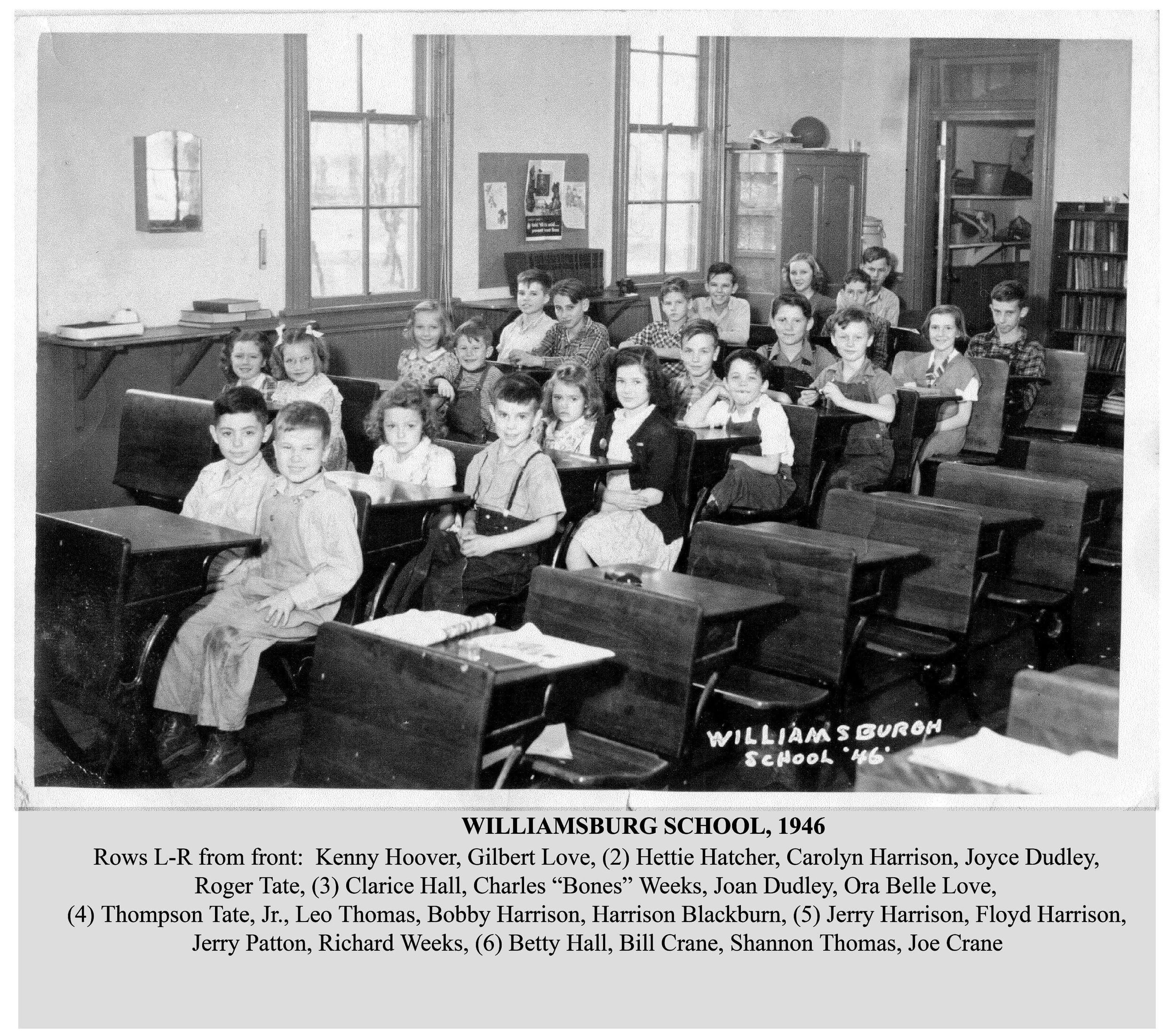

The school in Williamsburg, 1946.

At recesses—one in the morning and one in the afternoon—and after lunch, students would scatter in the school yard to play, and the teacher was always there to make sure all went well—to treat scuffed knees, separate and discipline the occasional fight, and, of course, to call balls and strikes. Few dared argue with the ump.

At the end of the day, students helped take blackboard erasers and beat them together to clean them of chalk dust. They took wet rags to wipe the blackboards clean. They spread lime in the outhouses to keep odors bearable.

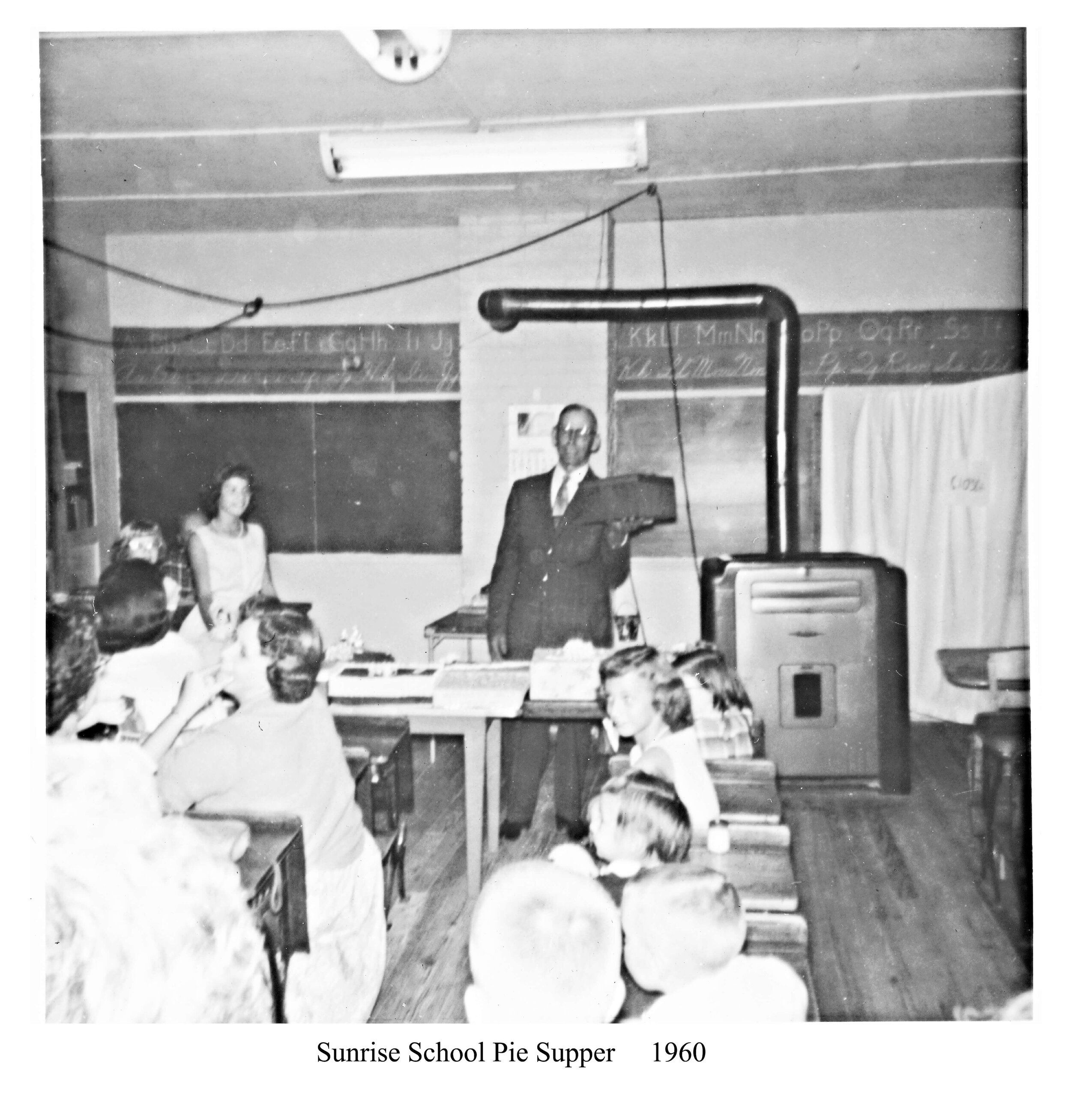

As with all schools today, the one-room school was also the center of the community, a place where suppers and school Christmas parties—always with a school play—were held. Extension and 4-H clubs often met there.

With the advancing years, roads got better and electricity came to the rural areas. Horses and walking gave way to school buses. By 1950, several schools had closed because educators believed students would receive a better schooling in town. Brown school, district 59, just a few miles south of Fulton was the last one-room school to close in 1974. The era when these simple schools could be found throughout the county every two miles was suddenly over.

"There is much to be said in favor of one-room rural schools," says Danuser. "But perhaps the larger schools are better for our children."

With all due respect to Ms. Danuser, most students of those days would disagree with her. They will cite receiving solid fundamentals in education, loving attention from their teacher and an unparalleled sense of community that their school provided. That feeling will stay with them their entire lives.